by William J. Holstein

by William J. Holstein

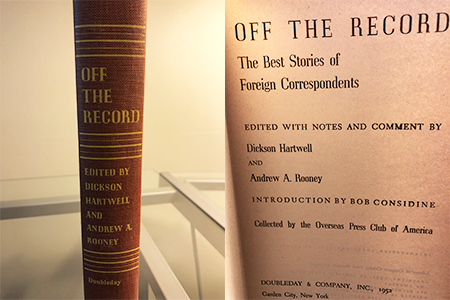

In Off The Record: The Best Stories of Foreign Correspondents, published by the Doubleday & Company in 1952 on behalf of the OPC, we can hear concerns being expressed about the number and quality of foreign correspondents working for American news organizations nearly three-quarters of a century ago.

In a preface, Russell F. Anderson, McGraw-Hill’s influential foreign editorial director, complained that following the end of World War II, so many correspondents returned home at the very moment that the United States needed their expertise to guide U.S. policy in the world, including in the conflict in Korea. There were 2,700 U.S. correspondents overseas in 1945 but by the beginning of the 1950s, that number had shrunk to 350. “Failure of the country to have trained observers abroad during a time of world crisis and transition seems to be self-evident danger,” Anderson wrote. He decried what he called the “firehouse technique,” more commonly known today as “parachuting” correspondents into a hot story and then pulling them home when the story is over. “The days of the swashbuckling, hard-drinking, hell-bent-for-action correspondent has all but disappeared – but nevertheless, foreign reporting has remaining an exciting profession,” he wrote.

Andrew A. Rooney, listed as a co-author, is in fact Andy Rooney of 60 Minutes fame. He covered World War II, but his voice is not immediately evident in the book. His role appeared to be confined to collecting the tales of others.

Bob Considine, the club president from 1947 to 1948 and 1954 to 1955 who is honored with an OPC award in his name, foreshadowed one of the debates that has raged until this day – the role of women in covering conflict. The Korean War’s contribution to “the realm of war correspondents has been the arrival of The Ladies.” There had been a handful of female correspondents covering World War II, he noted, “but in Korea they have landed with both feet, and if they aren’t in war to stay, I’m a monkey’s aunt.”

Marguerite Higgins of the New York Herald Tribune was one such intrepid correspondent. “One day while out on a dangerous patrol action, Miss Higgins and the handful of troops she was following were pinned down by a heavy mortar attack,” Considine wrote. “She and a young GI hit a ditch simultaneously and lay there close together as the enemy shells moved closer and closer,” he wrote. It looked like they would be killed. “In this awful moment Miss Higgins is reputed to have said, ‘Well, I’ve had a full and interesting life. I don’t mind dying.’”

To which the young GI yelled, “Maybe so, lady, but, goddamnit, don’t go including me.”

Another good tale is told by another female correspondent, Beryl Kent of United Press, which had not yet merged with the International News Service and was known simply as UP, not yet UPI. “I claim to be the only reporter who ever launched thirty-two warships with a short crimped bobby pin,” she wrote.

She was covering a drawing of lots among representatives from the United States, Britain, Russia and China to divide up 32 Japanese warships. The date was July 17, 1947 and the Japanese had been defeated. The four allies were dividing the spoils of war. “Division was to be made by lot drawing and each nation had sent a distinguished representative to do the picking,” she wrote.

But somehow the device that was distributing the folded pieces of paper, each representing a warship, jammed. “Then this reporter came to the rescue,” Kent wrote. “I let my hair down and donated the bobby pin [that was holding her hair up]. While three top-ranking brass delegates looked helplessly on, the fourth sheepishly used the copper bobby pin to extract the folded piece of paper, releasing thirty-two ships.”