by OPC Past President William J. Holstein

by OPC Past President William J. Holstein

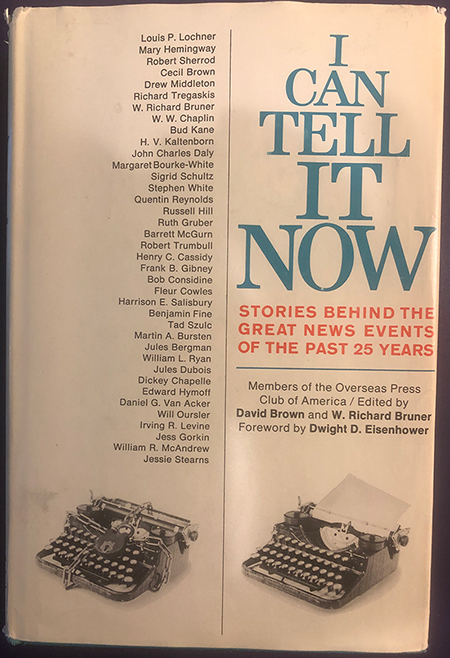

I Can Tell It Now: Stories Behind the Great News Events of the Past 25 Years. Edited by David Brown and W. Richard Bruner. 1964

This book, which the OPC acquired as a result of an anonymous donation, is a collection of 38 compelling stories written by OPC members about events they covered starting in 1939, the same year the club was founded. The mere fact that the book was published by a commercial publisher (E.F. Dutton) and included a foreword by former President Dwight D. Eisenhower speaks volumes about the prestige the club possessed at this high-water mark in its history. The club had a Book Publishing Committee consisting of top publishers including Bennett Cerf, the president of Random House. The book was published on the 25th anniversary of the club’s founding.

The first story was written by Louis Lochner, who spent an incredible 21 years covering Germany for The Associated Press from 1921 to 1942. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 1939 for his dispatches from Germany. He must have won the prize for his previous coverage because the story told in this book is about the German invasion of Poland, which occurred on Sept. 1, 1939. The Nazis used their advanced armaments, including tanks, artillery and fighter planes, to stage their “blitzkrieg” against Poland, but they kept Western correspondents out of the country. The outside world did not understand the brutality that Hitler had unleashed.

The Nazi propaganda chiefs became angry when Polish and French newspapers ran stories on Sept. 4 stating that German bombs had destroyed the Black Madonna of Czestochowa. This was a portrait of the Virgin Mary on dark cypress wood that had turned black, hence the name. It had been on a church altar since 1392 and was one of the most sacred religious symbols in Poland. The Nazis, in Berlin, wanted a wire service reporter to go see that the Madonna was untouched. Lochner was tapped to go.

The propagandists wanted Lochner blindfolded so that he could not see what was happening in the areas around the church. But once he was in the military theater, a colonel declined to blindfold him. As a result, he witnessed the full horror. “We faced and passed thousands of Polish civilians flooding back toward their homes, now that firing in this sector had ceased,” Lochner wrote. “A heart-rending procession of miserably humanity it was: barefooted women with their babes tied on their backs and their one lean cow trotting behind them…”

Lochner got to the church and, in fact, the Madonna had not been scratched. But how could he get his dispatch about the complete devastation out to the world? The way he did it was by burying a paragraph about the Madonna being safe in a much longer dispatch. The Nazi censors wanted to disprove the Madonna reports so they let it through. And for the first time, the world understood what the Nazis were doing in Poland.

Mary Hemingway tells an equally gripping story about being in London in 1940 during the German bombing campaign. (Her name was Mary Welsh at the time but after the war she moved to Cuba and married Ernest Hemingway.) She worked for a variety of news outlets but ended up at Time/Life. I never knew that British authorities censored American dispatches of the impact of the German bombs. The British wanted American help but they didn’t want word to get out, and back to the Germans, about just how devastating their bombing campaign was. German bombs knocked out London’s main sewage disposal plant and raw sewage was flowing into the Thames “which became a great stinking open sewer,” Hemingway wrote. Thousands of Londoners were sleeping in the subways, or tubes as the English call them, without adequate sanitation, creating other unpleasantness. “I can still remember walking home in the black and trembling streets beneath the noisy sky, listening for a bomb’s scream to end in its bursting, watching the fires, washing off and shampooing out the stench of the sheltering tubes.”

Members will recognize some of the other bylines: Ruth Gruber, Frank Gibney, Bob Considine, Harrison Salisbury, Tad Szulc, and Will Oursler. It is a whirlwind tour of history.