by Bill Holstein

by Bill Holstein

An anonymous donor has given a collection of about 40 books to the OPC. The most interesting are:

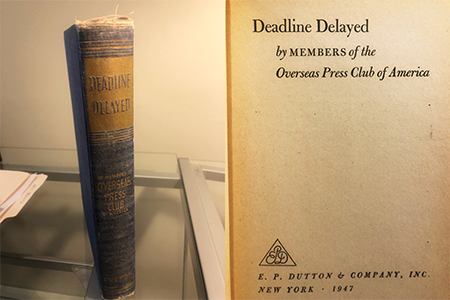

- Deadline Delayed. By members of the Overseas Press Club of America. 1947. A collection of 22 tales about covering stories in Europe, the Soviet Union, South America, Arabia, Lebanon and other locations.

- Off The Record. Edited with notes and comments by Dickson Hartwell and Andrew A. Rooney. Introduction by Bob Considine. 1952. A collection of World War II stories by correspondents.

- Seven Years in Tibet. By Heinrich Harrer. 1953. Harrer was not a journalist but the book became the basis for the movie of the same name.

- The Silent War in Tibet: The unknown story of the most remote and romantic nation in its struggle against the modern might of China. By Lowell Thomas Jr., son of our Lowell Thomas, who traveled with his son through Tibet. 1959.

- Asia Is My Beat, By Earnest Hoberecht, of the old United Press. 1961. Hoberecht was the first correspondent to reach Japan after World War II. He talks about war crimes trials in Japan, General Tojo and his interview with the last Emperor of China, among other stories.

- I Can Tell it Now: Stories Behind the Great News Events of The Past 25 Years. Members of the Overseas Press Club of America. 1964. Edited by David Brown and W. Richard Bruner. Foreword by Dwight D. Eisenhower.

We will run a series of mini-reviews of these books, starting this week with Deadline Delayed:

The Club had an Editorial Committee of six members who collected the stories by OPC members. All proceeds from the sale of the book went to the Club’s Correspondents’ Fund. “In a day when there is a growing world movement to remove the shackles which have all too often hobbled the news, the Overseas Press Club of America offers this book in the interest of freedom of the news, in every land and at all times,” Club President W.W. Chaplin wrote in an introduction.

Two of the most familiar bylines were those of Bob Considine (for whom an OPC award is named) and Irene Kuhn (for whom an OPC Foundation scholarship is named).

Considine wrote about covering the first test of an atomic bomb against warships, conducted at Bikini Atoll on July 1, 1946. About 200 journalists from around the world sailed for 17 days from Oakland, California, about the Navy’s observation and communications ship, the Appalachian. The reporters were given thick black goggles to watch the test. “It burst, low on the horizon, and it was an unforgettable apparition,” Considine wrote. “Though we could barely see the brilliant sun itself through the heavy glasses, the tiny core of the atomic flash burned brightly through our lenses and out of that terribly intense little piece of light there emerged a dome of lesser light.” He described the flame, smoke and steam the bombing generated.

Kuhn wrote movingly about traveling with American war crimes investigators to visit a cemetery outside of Shanghai where Japanese military forces had held—and executed—some of the Doolittle flyers from the U.S. military. These fliers conducted bombing raids on Japan but did not have enough gasoline to return to their ships. So they continued on to China and parachuted to land. Some were fortunate to fall into Chinese hands; others, however, were captured by the Japanese. Kuhn was presented with boxes of their ashes and personal effects.

The club’s executive director, Patricia Kranz, is working on ways to digitize the club’s historical artifacts once the pandemic is over and to possibly donate books and papers to Columbia University.