by Bradley K. Martin

by Bradley K. Martin

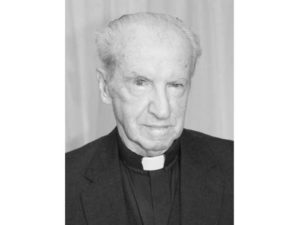

James P. Colligan, a Roman Catholic priest and a longtime member of the Overseas Press Club (OPC) and Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan (FCCJ) who died at 90 on Jan. 31 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, had something in common with Cold War-era journalistic contemporaries who represented government-funded news organizations ranging from VOA and Stars and Stripes to Komsomolskaya Pravda and Novoye Vremya, and who did not wish to be – or to be seen as – anything less than first class correspondents.

Father Colligan was determined to show that church-sponsored journalism was the real deal. Representing UCAN (Union of Catholic Asian News) and then CNS (Catholic News Service), he threw himself into both reporting good stories and participating in the professional activities that help make good stories possible. He served three terms as chair of the Foreign Press in Japan and was elected to the FCCJ’s board.

“Jim was on my board,” recalls Mike “Buck” Tharp, Club president 1989-90. “Just as he always was while sitting at a table in the Main Bar, Jim was often the grownup in the room. He was measured, polite, intelligent and empathetic with a subtly wicked sense of humor.”

Coming from what he described as a working class family in the ethnic mixing bowl that was Pittsburgh, Jim Colligan had an explanation for his healthy lungs despite exposure to the tobacco smoke that used to fill the Club’s bars: In the American steel capital he’d awakened each morning to find soot on the family’s window sills.

Colligan went to college at Duquesne University and enjoyed the dating scene. He even came close to marrying one woman – but before that could happen he realized he had a religious vocation. Of course Catholic priests must take vows of chastity and so, he recalled, he “said a sad goodbye” and went off to the seminary of the Maryknoll Society.

In 1955, after his ordination, Father Colligan was posted to Japan as a Maryknoll missioner. He studied Japanese and carried out parish priest duties in Sapporo and Kyoto parishes. For four years he was a pastor and kindergarten principal in the coal-mining town of Mikasa in Hokkaido. At the same time he taught English at Hokkaido University’s Iwamizawa Division.

He took time out to study journalism back in the United States, at Syracuse University, then returned to Japan as a journalist. Besides writing for the Catholic news organizations, he also did a column for a Protestant publication, Japan Christian Quarterly.

He edited a book called The Image of Christianity in Japan: A Survey.

A highly accomplished photographer, he published a book of photos of the 1981 visit to Japan by Pope John Paul II.

Non-religious news stories he covered included the 1992 visit of President George H.W. Bush. When the president fell ill at a state dinner, Colligan was there.

He was a fixture evenings in the Main Bar, where he exhibited his artistic talent by constantly sketching cartoons on the backs of drink coasters. He and the late Richard Pyle of the AP “scribbled lots of cartoons, often funny ones,” recalls former Club board member Toshio Aritake. Some of those cartoons, signed “Japacol,” made it into Number 1 Shimbun.

“He showed that dry wit,” agrees Tharp. “He drew one for us – ‘The Buckboard’ with me at the reins and caricatures of our board members in the wagon.”

A topic he kept returning to in conversation was the pigeons that made sleep in his Tokyo apartment difficult and repeatedly fouled his balcony. To hear him talk, you’d imagine he went after them relentlessly but haplessly – the way Wile E. Coyote pursued the Roadrunner.

Club colleagues didn’t hesitate to consult him on the relevant theology. Animal lover Mieko Yasuhara, longtime translator of the “Vox Populi” column for Asahi, was given to feeding the pigeons on her own balcony. A graduate of a Catholic school, she asked whether cats have immortal souls – and, if so, whether Father Colligan would baptize her cat Kobayakawa. “No,” he replied, unfazed.

“It was all good fun,” remembers Yasuhara’s husband, former Club president Roger Schreffler. “The club had an auction for some reason, I can’t recall why or when. Jim donated more than a hundred of his coasters. I do remember that I bought one on which he had drawn a pigeon.”

Although he seldom wore clerical collar in the Club, Colligan, with his chiseled Irish looks, could have been Hollywood casting’s version of a handsome priest. As Schreffler puts it, “he was dapper, the most eligible bachelor some might say.” Or, as Colligan himself would have protested, ineligible.

Often asked to handle delicate Club legal issues, Colligan liked to say, tongue in cheek, that he did so in reliance on “canon law.” In one such instance in 1993, recounted in the official club history, president Lew Simons asked Colligan to deal with a dispute over regular membership qualifications.

One irate member “promptly sent Simons a fax complaining that the problem should be handled by a regular correspondent and not ‘by a fucking missionary.’ Simons handed the message to Colligan, who was sitting next to him in the bar. Colligan smiled and said, ‘No, no. I’m the unfucking missionary.’ Colligan eventually was able to defuse the issue.”

Even though his eyes might twinkle when he referred to his priestly vows, he was dead serious about them. That was a major factor when, ultimately, Colligan-style journalism apparently became too probing to suit some superiors in his religious order. The work that upset Maryknoll bosses was on a topic less often addressed at that time than it is now: sexual scandals involving priests.

Father Colligan started with noting that, starting in the 1960s and ‘70s when a shortage of American priests had become evident, Maryknoll had made gays feel welcome in the clergy. There then arose a problem, he said, in that priestly abstinence was no longer enforced rigorously. His was the old sauce-for-the-goose argument.

“I understand priests who marry because they find it impossible to live under their earlier vows, but I do not understand homosexuals who make similar vows and stay.” he wrote for the Catholic magazine Crisis in a 1991 article, entitled “Gay Times at Maryknoll,” an article that still attracts new readership and online comments. “Apparently they feel either that their lifestyle is congruent with that of the society or that even if it isn’t, no one really cares.”

Reporting on questions of that sort more than a decade later brought Pulitzer Prize recognition to the Boston Globe and, still later, won the movie Spotlight the Oscar for best picture.

Such was the level of concern about Colligan’s challenge that his superiors ordered him home for a psychiatric examination. When talking with fellow FCCJ members, he compared the experience to something that would have been inflicted on a Soviet dissident. He described his stay at the order’s New York-area base as akin to house arrest.

Eventually, in 1997, Father Colligan wangled a career-capping assignment to Los Angeles. Jim Palmer, former AP photojournalist, and his wife Pamela were among Tokyo friends who had already moved to L.A. Pam Palmer relates that they helped him find an apartment and that he had “a swell time.” Colligan led Sunday services at a couple of churches and, in his spare hours, rode his bicycle, hung out with the Palmers, Tharp and ex-UPI Tokyo correspondent John Needham and became a champion (in his age group) skyscraper climber.

He returned to Maryknoll’s headquarters in Ossining, NY, to live in the society’s retirement home for a couple of years. Then, after cerebral incidents and an eventual diagnosis of dysphasia, he moved back to Pittsburgh – by then a city cleaned up, gentrified and quite pleasant. His final two years, during which he went silent on social media, were spent in assisted living there as some of his many relatives helped look after their beloved brother and uncle. “The adventurous life that he led was something that touched my entire family,” a nephew, Shawn MacIntyre, said in a eulogy.

Former OPC member Bradley Martin most recently is the author of Nuclear Blues, a novel set in North Korea in the near future.