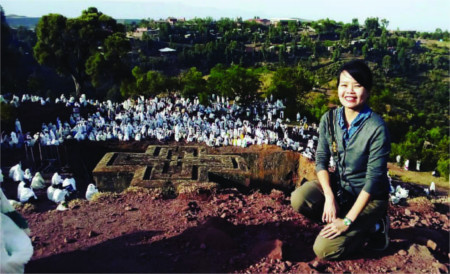

Yee views a Christian religious service at the Church of St. George’s, a rock-hewn monolith in Lalibela, Ethiopia. She struggles to garner interest among editors in stories that are not about bleak living conditions and violence. Photo courtesy of Amy Yee

by Amy Yee

Download the entire issue of Dateline here >>

At a prison in Thiès, Senegal, a group of women in fine dresses cut from the same colorful fabric enact a scene before an audience. One of them breaks down sobbing and wailing; another woman comforts her. These women are not actors, but female inmates of the prison depicting why many of them are in jail: infanticide and abortion, which is effectively illegal in Senegal.

It was International Women’s Day and the women were sharing their stories in front of dignitaries, diplomats and activists. Later, I spoke with a soft-spoken inmate. She was 40 years old and was locked up after the death of her seventh child. “Mariama,”, as I will call her to protect her privacy, denied killing her baby and said he died at birth. Yet she was serving a seven-year prison term for infanticide after awaiting trial for three years. Mariama said coping with family and children she left behind was one of the hardest things for her. “They don’t understand what you’re going through,” she told me quietly.

When I interviewed Mariama, I didn’t want to just write about the unspeakable tragedy of a mother killing her child in a poor country. “What could prevent such a desperate act?” I asked a program officer with Tostan, an NGO that works at that jail and with women prisoners. Her answer was simple: family planning.

In Senegal, as in other developing countries, some poor, rural women do not know about birth control and those who do often lack access to it. The program officer recalled one female prisoner who broke down in tears when she learned about contraceptives. If she had had access to them, “I wouldn’t have had to kill my baby,” she cried.

It is tragic that women have to resort to infanticide and are jailed for abortion in Senegal, whose cosmopolitan capital Dakar gives the impression of a relatively developed nation. In fact, nearly half the country lives below the poverty line, which can lead to desperate measures. [https://www.worldbank. org/en/country/senegal/overview]

But Senegal has been making progress in expanding women’s access to family planning through education, outreach in rural areas, better-equipped clinics and more health workers. West Africa claims some of the world’s highest birth rates, but through family planning Senegal brought its rate down from 6.4 children per woman in 2011 to 4.9 in 2014.

Advocacy groups in Senegal have been raising awareness with policy makers and judges who mete out harsh sentences without understanding the desperate circumstances– rape, incest, extreme poverty–that women who have abortions face. Some of that progress is being hampered by a U.S. policy to cut funding for women’s reproductive health.

My article that featured Mariama was not about terrorism, war, deadly epidemics, famine or disaster–topics that dominate headlines from Africa and developing countries. Of course, those issues and events are hugely important and the world must know about them. But the world should also know about other vital stories that aren’t about bleak living conditions and violence.

The story of Senegal’s progress in giving women access to reproductive rights and better health care is critical for bringing its birth rate to sustainable levels, and in sub-Saharan Africa as a whole for avoiding crises of overpopulation, job scarcity, food and water insecurity and more. Describing the desperate measures taken by women in the Senegal prison was just the start. Writing about what can be done to prevent a terrible problem was just as important. However, in an era when news churns at a head-spinning pace, this nuanced story doesn’t check the “easy-to-understand” box. I pitched this story many times to multiple outlets; it took a year to find a good home for it in The Lancet.

The articles I’ve written from 11 countries in Africa over the past two years are not about terrorism, armed conflict and disaster. There are many excellent journalists doing this important reporting. I focus on less covered but no less important stories that should be heard. Yes, editors are busy (as are reporters and freelance journalists on the ground in risky environments), but they should be open to stories that don’t fit the mold of conflict and disaster, and that don’t hew to archetypes and stereotypes.

Another boon to journalism would be more media outlets, pages, or web ‘verticals’ that spotlight these stories. Instead, media outlets are being forced to shutter pages devoted to international news, environment, education, culture and other important topics. Many of the pages or publications that I used to write for are gone. And sadly, in these tumultuous times, an alarming number of media outlets are shutting down entirely or cutting already-scarce jobs.

Developing countries face a litany of urgent problems, from climate change, deadly diseases, environmental destruction, armed conflict and violence against the vulnerable. These problems usually seem entrenched and hopeless, so I am intrigued when I find promising initiatives that tackle or mitigate them. I go out of my way to write these stories.

From eastern Congo, one of the worst conflict zones in the world, I wrote a long feature analysing efforts to harness small hydropower to create electricity, which will hopefully create jobs and a better chance at stability. This was a story for the Sunday Business section of The New York Times, but still very much about people suffering from lack of jobs, deep poverty, political instability and poor governance. Another story, also for the paper’s business section, analysed the enormous potential that renewable geothermal energy could have in Kenya and the region–and the very real obstacles to realizing its potential.

Of course, the obstacles to alleviating social problems are enormous and many efforts fail. There should be more initiatives and more progress on many fronts. I know firsthand that newspapers and magazines are strained and there aren’t enough pages or resources for international news. But promising stories from developing countries about business, science, technology, public health, arts and culture are fascinating to read and have real impact.

Children don’t have to die of careless drowning in Bangladesh. People in Rwanda don’t have to decimate forests for cooking fuel; there are alternatives. A small-time poacher in Kenya would readily give up that work for a safer, regular salaried job. A poor woman in Senegal doesn’t have to kill a baby she cannot support if she can plan her pregnancies.

Those are some of the initiatives I’ve been honored to write about. Under ideal circumstances, spotlighting what can be done to remedy myriad problems could alleviate or even prevent the tragedies that create headlines. It’s not easy to get editors to understand and give attention and diminishing space to these nuanced stories, but they must be told.

Amy Yee is an award-winning journalist who writes for The New York Times, The Economist and NPR. She is a former staffer for The Financial Times based in New York and India, where she lived for seven years. Amy is a three-time winner of the United Nations Correspondents Association award and four-time winner of the South Asian Journalists Association award. Her work is at Amyyeewrites.com.