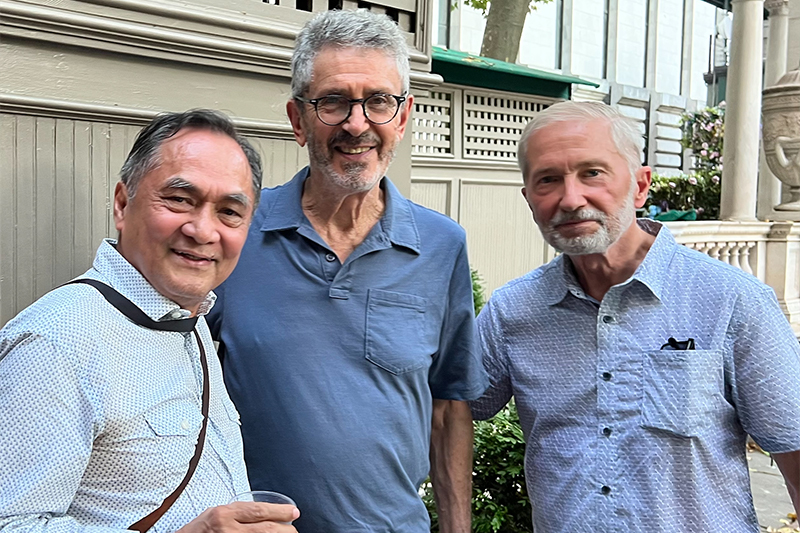

Longtime OPC member Jaime FlorCruz visited New York in late July, gathering with a group of club members at the Bryant Park Café to chat about his new book, The Class of ’77: How My Classmates Changed China, and to toast the efforts of OPC President Paula Dwyer and Executive Director Patricia Kranz in guiding the club through two years of the pandemic. Below is a review of FlorCruz’s book by OPC Past President William J. Holstein, who also attended the gathering.

by William J. Holstein

When I was based in Beijing for United Press International in 1981 and 1982, those of us who lived in China had a joke about all the dignitaries and sages who would come to town. If some of them spent two weeks in China, they could write books about the place. They were so certain of their conclusions. But if they spent two months in China, the most they could manage was a magazine article because they would be forced to acknowledge their inability to peer behind the curtains. But if someone lived in China for two years, they couldn’t write anything. They were just flat out confused.

So, it’s nothing short of a miracle that Jaime FlorCruz has produced a book about his 50 years of living in China. He was a left-leaning Filipino student activist who went to China on a study mission in 1971, when the regime of President Ferdinand Marcos put him on a blacklist of dissidents, forcing him into a 12-year political exile. But he decided to study Chinese and immerse himself in Chinese culture. He enrolled at Peking University in the class that started in 1977, hence the book’s name, The Class of ’77: How My Classmates Changed China. FlorCruz was working for Newsweek when I arrived. He eventually jumped to TIME magazine and then CNN.

FlorCruz lived through incredible upheavals – the Cultural Revolution did not end until 1976 when Deng Xiaoping re-opened universities that had been closed during the ideological struggle. FlorCruz did physical labor on a farm and on a ship. Then came the Tiananmen Square protests and massacre in 1989. The economy, meanwhile, exploded and China surged into the ranks of advanced industrial nations. Xi Jinping started consolidating power in 2012 and has created the world’s first digital dictatorship while advocating for “common prosperity,” one of the new rallying cries. It turns out that Xi is an old-fashioned Marxist who believes Communism will triumph over capitalism.

“No one really knows what the Communist Party is ultimately about,” FlorCruz wrote. “With its ninety million members, it remains the most efficient political organization in the country and possibly the world. … The Maoist vision of a Marxist, egalitarian paradise is viewed by many Chinese as irrelevant to their lives, which is all about making money, encouraged by Deng’s admonition to ‘allow some people to get rich first.’”

For that reason, Xi’s new emphasis on common property “requires yet another radical shift in the Chinese mindset,” FlorCruz wrote. Increasingly, the Chinese are “searching for a moral compass, a mooring.”

Aside from common prosperity, Xi is trying to instill Chinese nationalism in the soul of his people, which FlorCruz calls “a dangerous prescription.” Xi harps on China’s “century of humiliation” starting with the British Opium Wars in the early 1840s up until Mao Tse-Tung’s victory in 1949. “Hence, the nationalist push and popular support for a strong state, including acceptance of its more intrusive surveillance powers,” FlorCruz wrote. “China has to be strong in order to face down its foreign enemies, and that means everyone at home must behave and toe the line.”

Will Xi engage in more outright aggression against his own people and neighbors? Of course, no one knows and FlorCruz is wise enough to accept the lack of clarity: “China is a cocktail of contradictions,” he wrote. “It remains hidebound in ancient tradition and conventions, and yet it is quick to embrace new concepts and practices. It’s one of the oldest civilizations, and yet it is still trying to catch up with others as a modern, developed country.” To revert to a joke that wire service hands used to tell when confronted with too much complexity, “only time will tell.” That’s doubly true when it comes to China.