by William J. Holstein

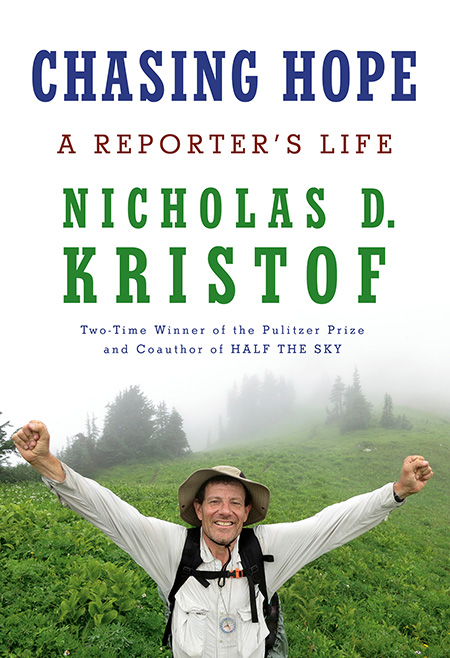

If you have ever wondered what motivates a journalist such as Nick Kristof to travel to hellholes such as the Sudan’s Darfur region, Myanamar and Yemen, or to ride his bicycle into the middle of the Chinese army’s crushing of pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989, then you will be intrigued with Kristof’s latest book, Chasing Hope: A Reporter’s Life.

Kristof’s motivations were shaped by the fact that his father was a refugee from the horrors of World War II in Europe. He was an Armenian Catholic living in North Bukovina, which is part of Ukraine today, and used the Polish version of his name, Wladyslaw Krzysztofowicz. He suffered at the hands of both the Soviets and Nazis and risked his life on multiple occasions to escape to America, sponsored by the First Presbyterian Church of Portland, Oregon.

Kristof’s mother was from Chicago and the family moved from Chicago to New York City to Palo Alto to Waterloo, Canada, before both father and mother were able to get jobs at Portland State University back in Oregon. The two of them obviously believed in religious and intellectual freedom, not to mention freedom from enslavement and persecution. “A tortuous family history helped turn me into the kind of reporter I became,” Kristof wrote. “We Kristofs were spies, prisoners and refugees, and we were rescued by strangers.” Elsewhere, he writes that he believes in “purpose-driven journalism that exposes injustice.”

Nick’s parents were able to buy a farm in the remote farming community of Yamhill. He was an odd duck at school because he didn’t fight or shoot guns, but he formed a deep connection with the land. I recently visited him, walking through some of the 200 acres he owns with wife Sheryl WuDunn, once a fellow New York Times reporter. It is planted with 20 acres of apples that he and WuDunn use to make cider (available at KristofFarms.com) and with wine grapes.

He and WuDunn won an OPC prize in 1990 for their coverage of the Tiananmen Square massacre, just before also winning a Pulitzer. Living for five years in China obviously left a deep impression on him and affected the way he sees his own country. “In recent years in the United States, as democracy has struggled, as some elected leaders and television pundits seemed more committed to undermining democratic government than to preserving it, I’ve thought often about those Chinese who risked everything in their failed bid for greater democracy [at Tiananmen],” he wrote.

Kristof has been a leading crusader on the subjects of child sex trafficking and the genital mutilation of young women in Africa, and is critical of the American foreign policy establishment for not caring more about those issues. He wrote that the “graying doyens of the Council on Foreign Relations” can scarcely bother with the subject of female genital mutilation.

He also remains a critic of former President Donald Trump and faults the news media for “bothsidesism,” meaning quoting one side of an argument and then the other when it’s clear that Trump often tells flat-out lies. He also offers insights on the internal politics at the Times, such as the firing of editorial page editor James Bennet for running an op ed from Senator Tom Cotton, urging a crackdown on protests against racial violence, and the firing of health reporter Donald McNeil for using “the N-word” in a discussion with students about racism. Kristof was against both dismissals.

His book ends with an insider’s account of how Kristof ran for governor in Oregon but was disqualified. Yet, he was able to make the transition back to the Times. All in all, Kristof’s life story is fascinating and should be an inspiration to aspiring journalists everywhere.