by Irwin Chapman

by Irwin Chapman

Part I

My father was a news junkie, therefore I became one. We listened on the radio to Edward R. Murrow, of course, and the CBS “World News Roundup.” And there was a local New York commentator, George Hamilton Combs, who ended his daily 15-minutes: “And that’s the way the world spins!” It turns out that he was a founder of the Overseas Press Club.

My fifth grade teacher, Mrs. Goodman, turned us on to “current events,” and in the seventh grade at Hermann Ridder Junior High School, Mr. O’Kun taught journalism and got me on the student newspaper. The school was named after the proprietor ofthe Staats-Zeitung und Herold, so the Ridder News, was printed at the Staats-Zietung plant in lower Manhattan. Every month, after school, classmates and I went downtown to proofread after the linotypists set our stories in cast lead, put the columns into page forms, and sent them to the presses. We went home with hands blackened with printer’s ink.

During a school recess, I took the train to Washington. emerged from Union Station, walked toward the sunlit Capitol. I entered the Senate Office Building and found the office of my Senator, Jacob K. Javits, and asked to interview him for the Ridder News. He invited me in, after which I encountered the Senator from Minnesota, Hubert Humphrey, a hero to many liberal New Yorkers, and interviewed him.

On weekends, in addition to museums, I went downtown to a movie house that just showed newsreels, plus a 20-minute edition of “The March of Time,” or “This is America.” When the political conventions of 1948 were televised, I went to watch TV at the RCA Exhibit Hall on 49th Street; it’s now the “Today Show” studio. Years later, after his presidency, Harry Truman would come to New York or Washington occasionally for a Democratic Party event. He let it be known to the press where he was staying, and promptly at 8 a.m. he went out for his morning wal, fielding questions on whatever was in the news that day. If there was a cameraman along, he would have to walk backwards, and Truman would interrupt himself to warn the guy he was about to back into a lamp post.

I continued in student journalism in high school and enrolled at New York University which offered a major in broadcasting. After an introductory class that taught me how to edit reel-to-reel tape with a razor blade, I took the writing course, and thenswitched to a major in history. I became co-editor of the student newspaper in my junior and senior years and also campus correspondent for the New York Times. The City Hall reporter for the World-Telegram started a weekly program on the city-owned radio station, WNYC, inviting the politicians he covered to sit for a half-hour interview with student editors–including me. Gabe Pressman went on to become the quintessential New York television correspondent.

There was also a daily television program on NBC hosted by a popular singing star, Kate Smith, the Oprah of her day. One feature was a panel of student editors chatting about the news—again including me. On June 2, 1953, we were on the set waiting to go on. It was the day of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation in London. CBS and NBC were competing, in those pre-satellite days, to fly the first film to America. NBC was ready for air just as our segment was to begin. We were pre-empted. She is still the Queen; I am still a broadcaster.

After college and a semester in graduate school—international affairs—I was drafted, Thanks to the good luck of the draw, I shipped out to the idyllic town of Salzburg, Austria. I quickly found my way to the studios of the Blue Danube Network of Armed Forces Radio and spent the next year and a half as a staff announcer. A buddy and I made our first grand tour of Europe by train.

Returning to New York, I answered a want ad for a news writer and got the job at Radio Free Europe. On vacation in 1957, I took a tape recorder, which was twice the size and weight of a portable typewriter and ran on electricity, to Haiti, which was having a presidential election. I interviewed the two leading candidates, an assertive businessman, Louis DeJoie, and a mild-mannered physician, Francois Duvallier—who kept me waiting on his porch while he had his afternoon map. Duvallier went on to become one of the most brutal dictators in the world.

I also stopped in Cuba and did a feature on cigar factories where, instead of listening to a blaring radio, the workers chipped in to hire an actor to read books to them. I sold the the sound bites from both stories to NBC Radio, for a program narrated by Walter O’Keefe. It was called “Nightline.”

A year or so later, I read that a new radio news service was being started by George Hamilton Combs. Called Radio Press, its premise was that, with entertainment programming gravitating to television, local radio stations were ready to drop their network affiliations if they could get news spots from a low cost syndicate. I was one of the original hires. Combs sponsored my OPC membership.

I got to cover the 1960 Republican convention in Chicago—a colleague covered the Democrats in Los Angeles—and to watch a bit of John F. Kennedy’s campaign. To his young admirers, he was a rock star. They would trot alongside his open car and reach out to shake his hand or touch him. As he emerged from the car, one or both of his cuff links might be missing. I covered his appearance before Baptist ministers in Houston in which he assured them his Catholic religion would not control his decision-making.

On the evening of the first Kennedy-Nixon debate, September 26, 1960, my colleague, Bruce Morton and I, met for dinner, then got to my walk-up studio apartment just before the debate was to start. The door was ajar. A burglar had taken the television set. We had no choice but to listen on a portable radio. When it was over, we may have been the only journalists extant who thought Nixon had won the debate.

Radio Press had stringers in London (Norman Moss) and Paris (Bernard Kaplan) and initially used a Washington service run by a former wire service reporter, Herb Gordon, but then decided to create its own bureau. I was sent to Washington right after Kennedy’s inauguration. Dirksen, Russell, and Hart were Senators, not office buildings. Sam Rayburn was Speaker of the House. I looked at the office-space-for-rent ads and took a room that a Capitol Hill hotel called the Dodge House had converted to office space. I got my first Capitol Hill press pass, and also appointed myself White House correspondent.

There was no White House press room at that time. The few reporters who covered briefings by the press secretary, Pierre Salinger, sat on sofas in the west lobby along with other invited visitors. There was a large round table in the center of the big room, a gift of the Philippine government, where we threw our overcoats. If there was a ceremony in the East Room or the Rose Garden, I handed my recording cable (by then, recorders were battery-operated and the size of a book) to a staffer of the White House Signal Agency, one of whom was John Cochran.

I was at the White House during the suspenseful Cuban missile crisis in 1962. It was hard to believe that a nuclear confrontation was truly possible.

Kennedy held his news conferences in the auditorium of the State Department, and for the first time allowed them to be telecast live. There were serious issues to discuss, not the least being the growing insurgency in Southeast Asia and his decision to send U.S. troops into Vietnam. But he had a quick sense of humor. Asked about a Republican National Committee resolution that his administration was a failure, he quipped. “I assume it passed unanimously.” Asked what surprised him most when he got into office, he said it was “finding that things were just as bad as we’d been saying they were.”

Part II

In June, 1963, ABC Radio, which aired its newscasts at :55 past each hour, decided to program a news feature at :15, repeated at :25. I heard about it from a friend and was hired as the Washington correspondent. I would do one of the daily features and supply additional interviews to my New York colleagues. They included Jim Harriott, who had been a disc jockey at WMCA; Ted Koppel, a copy boy at WMCA; Stewart Klein, who later became entertainment critic for Channel 5; Charles Osgood; and Betty Adams.

The program’s staff was before long merged into ABC News. My first major special event broadcast was John F. Kennedy’s funeral. I was stationed beside the North Portico as his casket was brought from the East Room, a shattering experience. ABC Radio made a phonograph record of the coverage. It was years before I could listen to it.

I went on to cover the funeral of Robert Kennedy, a few days after I returned to Washington from covering a week of his campaign. On August 28, 1963, I was at the Lincoln Memorial when Martin Luther King gave his “I have a dream” speech. My assignment was to watch the periphery of the crowd for potential violence. There was none, of course. But when Dr. King was murdered, there was plenty.

To cover Congress meant sitting in the press area of the House or Senate Gallery, or at the press table of a committee hearing. C-SPAN started telecasting the House in 1979 and the Senate seven years later. On June 10, 1964, I was in the gallery when Republican Leader Everett McKinley Dirksen delivered the decisive speech to shut off the civil rights bill filibuster. And for State of the Union addresses, I stood in the back of the House chamber, microphone in hand, to introduce the live event.

I covered the civil rights movement in Mississippi and Alabama and was lectured by locals that the Black people were being manipulated by outside agitators abetted by the Northern press, and if we ignored them, tranquility would return. We were warmly welcomed, though, in the Black churches.

When ABC-TV expanded into syndicating film coverage, I started getting television assignments. To cover a hearing, we stationed a camera on the members’ platform—behind the minority, which meant filming the backs of their heads. A roll of film was 1000 feet, 33 minutes of action that also took 33 minutes to develop. I mastered the skill of signaling the cameraman when to film a Senator who might ask incisive questions of the witness, and when to shut off or take “cutaway” shots to enhance the edited “package.”

It was also the ethos of the time that all footage had to be fresh, If the story was about a spike in inflation, we had to take a camera crew down to a supermarket for “b-roll,” not dip into the film library. And b-roll was literally that; the film editor created an “a-roll” with the sound bites, narration, and standup, and the studio director had a cue sheet to switch between a-roll and b-roll to get the package on the air.

ABC News had only one White House correspondent, Frank Reynolds. So when President Lyndon Johnson travelled, I often got the call to backstop. That included visits to his Texas ranch, with the press room alternating between Austin and San Antonio, and most memorably, his visit to the troops in Vietnam in December, 1967, followed by his stopover in Rome to meet Pope Paul VI, who agreed to see him at the last minute.

In 1964, I was assigned to be a floor reporter at the political conventions.

ABC had just hired a young anchor, Peter Jennings, but his contract with Canadian television had not run out, so he couldn’t go on the air for ABC yet. Peter observed from the TV booth. When ABC-TV signed off around 11:30 p.m., the ABC Radio team assembled in the middle of the floor to keep talking until newscast time at 11:55. Peter came down, listened to us—my colleagues were Herbert Kaplow and Vic Ratner—and when we finished said, “I don’t think I’ll ever be able to do that.”

Before the 1968 conventions rolled around, ABC’s Moscow correspondent, George Watson, came to Washington on home leave and we had lunch. George said he’s been promised two years in Moscow, then out, but was well into his third year, and his boss said no one could be found to replace him. I told George that I had studied some Russian language and history, and was available. George didn’t quite spring from the table, but he reported back that salvation was at hand. I got the job.

At the time, a conglomerate called International Telephone and Telegraph was in the throes of buying the American Broadcasting Company. But members of the House Commerce Committee, among others, were raising alarms that a company with a defense industry subsidiary should not buy a network that covered the Pentagon. The deal fell apart, instead of a promised boost in the news budget, there was a cutback, including a freeze on hiring and transfers.

As a result, my assignment to Moscow was postponed to January. I got to cover the 1968 conventions, and from an unexpected—and very safe—perch. The ABC-TV producer didn’t care to staff the speakers’ podium, so I got that spot. While other reporters were teargassed in Chicago’s Grant Park and manhandled on live TV while doing interviews on the convention floor, I described the joyful reception the candidates got from the party VIPs as they left the speaker’s rostrum, and later learned the TV folks were using my commentary as well.

So my wife, Arlene, and I arrived in Moscow in the dead of winter, after a stopover in London to buy sheepskin coats. We moved into an apartment that had been sparsely furnished by the first ABC Moscow correspondent, Sam Jaffe, with the windows insulated by torn strips of newspaper pasted over the cracks with flour-and-water paste. Before the next winter, I ordered duct tape from Helsinki.

Foreign television bureaus could not hire their own camera crews. We had to ask an government press agency for a crew by describing in writing the story we wanted to shoot. If we got the OK, the crew came with a “coordinator,” an English-speaking traveling censor. If the final script I recorded gave offense, the film might not make it to the airport. Most of what we did was soft features, from women in the workplace to the puppet theater. When I did a story in a factory that made Soviet champagne, I filmed the closing “standup” in front of the bottling line. The “coordinator” couldn’t hear what I was saying, so he order the bottling to stop.

Doing a radio report meant going to a small studio in the central post office. Every once in a while, after I sat there saying “Hello New York” over and over until the ten-minutes ABC booked expired and I had to leave, I learned that ABC New York had been told by an unidentified Russian-accented voice, “Your correspondent failed to appear for the broadcast.” It was a relatively harmless example of the Russian ability to deal with a situation with an outright lie.

Then AT&T took full-page ads announcing that land-line phone service had been extended from Finland to Russia. My boss called, we hooked up our tape recorder to the phone, and for the rest of my stay in Moscow, I could talk straight to New York.

I was able to travel all over the Soviet Union, logging about 20,000 miles on Aeroflot’s Ilyushin and Tupolev airplanes. After the Soviets made a deal with Fiat to build a car factory, wee took a driving trip all the way down to Yalta for a feature on “Is the Soviet Union ready for the motoring age?” Everywhere we went, people were warm and welcoming. Outside of Moscow, no one realized that you could be deemed a security risk for consorting with foreigners. Our request to film the Fiat factory, however, was denied.

In my third year in Moscow, I got a surprise message. ABC Rome correspondent Barrie Dunsmore was in Calcutta, covering the flow of refugees from the war in East Pakistan that created Bangladesh, and he needed to be relieved. I was off to Calcutta. When I travelled in Russia, Arlene came with me. Flights, paid in dollars, were cheap. When I left for India, she left for Helsinki.

After Calcutta, I had an assignment in Germany. Then Egypt’s Anwar Sadat kicked the Russians out and reoriented to the West. Russian President Podgorny went to Cairo to dissuade him. Beirut correspondent Peter Jennings was on assignment elsewhere, and I went to Cairo.

Part III

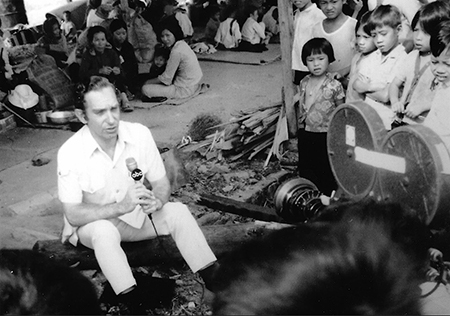

The Vietnam War was dragging on. ABC had been hiring new correspondents willing to spend a year in Vietnam and then get a slot in a domestic bureau. By 1971, the decision was made to send existing staff on three-month rotations. Arlene and I headed to the Caravelle Hotel in Saigon, and Sam Donaldson returned home.

The Vietnam War was dragging on. ABC had been hiring new correspondents willing to spend a year in Vietnam and then get a slot in a domestic bureau. By 1971, the decision was made to send existing staff on three-month rotations. Arlene and I headed to the Caravelle Hotel in Saigon, and Sam Donaldson returned home.

An election was in progress. Vietnam had some 30 newspapers, all but one complaining that the voting was rigged, quite a contrast with the press in Soviet Russia. Students at the university debated as though they were in Berkeley. Why were the Americans in their country? There must be oil reserves offshore. American money created a middle class. The war was at a low ebb. President Richard Nixon had announced that American forces would pull out after training South Vietnamese. Plainly, South Vietnam was a comparatively free country. The issue for me was how long could that last and what would happen to that middle class eventually.

During a vacation in Europe earlier, I phoned my Paris colleague, Lou Cioffi, who was bureau chief in Tokyo when I first met him in Saigon. Lou kept wired in to office gossip, and told me that the Tokyo bureau was again available. ABC News had hired a magazine reporter, sent him to New York for three months to learn television, it turned into five months, and they gave up. I wrote a letter on hotel stationary to the ABC television vice president. The day after Nixon left Moscow, Arlene and I flew to Tokyo.

Right after we arrived, there was an anti-Vietnam demonstration near a U.S. military base. I got together with the Tokyo camera crew and off we went. No more bureaucracy to deal with.

Japan was a great setting for television stories of every sort, from the world-beating auto and electronics industries to the brewing of sake, and beer. The “oil shock” of 1973 hit America hard. Drivers lined up art gas pumps when the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries declared an embargo. I was asked to film one story after another on how Japan coped.

The government ordered reductions in use of electricity, dimming the lights on Ginza, and gave “administrative guidance” to keep a lid on the price of kerosene, widely used in home space heaters. Above all, the Japanese had a long-standing tradition of group behavior and a feeling that being buffeted by outside forces was nothing new. Only their growing prosperity was new, and nobody said it would last forever.

But for most of my time in Japan, the major story was the Japanese economic system that drew the same complaints from U.S. companies that have more recently been directed at China. The government targeted favored industries, which then got cheap loans from banks that were part of the same conglomerate. The Japanese tried to import only what they themselves didn’t at that time produce, from sophisticated medical equipment to complex chemicals. Otherwise they erected subtle barriers that raised the price of imported goods, from Burberry coats to Buicks, to twice what they cost in the country of origin.

When the central bank tried to puncture a real estate bubble, the Japanese were flummoxed. The economy went into a two-decade slide.

Before he toured the United States in 1975 – including a visit to Disneyland – Japan’s Emperor Hirohito gave a press conference and then was persuaded to grant one-on-one interviews with the three American networks. I took a camera crew to the Imperial Palace. We were instructed to bring a vase of flowers and hide the microphone behind it, and the sound technician was positioned behind a screen.

The Emperor entered and shook my hand, limply. When it came to the major topic of Japan’s responsibility for World War II, Hirohito repeated tepid formulations, that he “regrets that most unfortunate war, which I deeply deplore,” and “there are certain things which happened for which I feel personally sorry.” It was hard to envision him as the fierce figure on horseback inspiring troops to die in his name.

I travelled all over Asia for news coverage, from martial law in the Philippines to a hijacking in Thailand, to floods in Pakistan, to American draft evaders in Australia. I took a camera crew for a fresh look at Vietnam. We filmed a story on everyday life there, and after it aired, the New York anchor, Harry Reasoner, wondered in his commentary, how many more years would the newscast send a crew to update the story.

The answer turned out to be less than one half of one year, when the North Vietnamese staged their final blitzkrieg and their Russian-built tanks rolled into the Presidential palace in Saigon. Refugees streamed south ahead of the tank column. The evacuation of American and other foreign personnel and Vietnamese employees had been going on for some days.

The three American television networks chartered a plane to take their Vietnamese cameramen, translators, office workers, and extended families to safety. The U.S. Embassy was slower to move, to concede that the cause was lost and it had to get people out. So numbers of Vietnamese staffers wound up in Communist “re-education” camps. I wrote then that it was better for a Vietnamese to have worked for the Bank of America than for the United States of America.

I was assigned to Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines, then to Guam, where refugee camps were organized. American employers set up help desks that connected the Vietnamese to charitable organizations sponsoring emigration to the United States. The TV networks placed their staff cameramen in Los Angeles and Washington bureaus, and got their stringers jobs at affiliated stations. And for days, months, years to come, Vietnamese piled into leaky boats to sail away from their benighted country to wherever they could start new lives.

The appetite on American television for overseas news – except when explosives were going off in view of cameras – is severely limited. Long before I became a foreign correspondent, ABC’s Paris correspondent, John Rolfson, told me about the “Home-on-Wednesday syndrome.” He would be assigned to cover a story in Africa or the Middle East, send a message to New York on a Friday that the story was done, could he go home? The reply was to hang on through the weekend just in case. After New York’s Monday editorial meeting, he would get the OK to leave, but the message would arrive after Tuesday’s flight departed, so he would get home on Wednesday. That would be my experience years later.

Meanwhile, my colleagues in domestic bureaus went out in the morning and back the same night, or they were away a couple of days to cover something the whole country cared about. So it appeared to be time to return home.

When we first found ourselves in Moscow, Arlene and I and I looked at each other for weeks and said, “What have we gotten ourselves into?” Returning to a provincial U.S. bureau, we were asking ourselves the same question from the get-go.

Even editor-producers, not just neighbors, when they asked about our foreign experience, if we went on longer than a minute, eyes glazed over.

Foreign cultures go back centuries, evident not only from ancient castles on hilltops but from the attitudes inculcated by tradition, attitudes toward family, friends, classmates, local leaders and central governments. A foreign correspondent is always an outsider, but often a welcome onlooker. Back home, except for Washington, national news is often centered on crime and weather, not a constant learning experience.

During my New York intervals, I attended OPC events, including an awards dinner anchored by Peter Jennings. When the OPC had a place to hang out, I was there on visits. I enjoyed OPC reunions of former correspondents from Moscow, Tokyo, and Saigon. And I led a panel discussion with Ted Turner as one of the participants. When it was over, Turner said to me, “You ought to come work for me. You won’t make much money, but you’ll have fun.” It didn’t seem a great idea at the time.

But the most significant benefit that the OPC offered me was back before airline deregulation, when the way to get an affordable flight to Europe was to be a member of an organization that chartered an airplane—which the OPC did. You had to book six months ahead, so i reserved a seat for the flight leaving on May 20, 1965. As that date neared, Arlene agreed to marry me. So I called the chairwoman of the OPC flight committee to see if a second seat was available.

She said she had just had a cancellation, reminded me that i was only allowed to bring a family member or the airline could be fined and would ban the club from further charters. I said I was being married at noon of the departure day. She told me to bring her the marriage license.

When we arrived at the TransWorld Airlines terminal at JFK, we were greeted by the then-president of the Club, Merrill Mueller, and a TWA PR guy and his photographer. And on board the flight, after dinner, the purser asked us all to remain seated for an additional service: a wedding cake. TWA was our favorite from then on. The airline folded, but we are still married.

We finally made our way back to Washington, after another detour to ABC’s New York headquarters. When ABC News contracted at the behest of its new owner, Capital Cities, after a hiatus, I was hired as a Washington correspondent for CNN Business News, working for Ted Turner’s company after all.

When my then-bosses, after six years, insisted on a move back to New York, where the work consisted of interviewing stock analysts, I sent my resume around the industry. A former news director for WABC-TV whom I didn’t know was working for Bloomberg, Paul Ehrlich, saw it and urged his boss to hire me as their first Washington TV correspondent. The final step in those pre-mayoral days was a personal interview with Mike Bloomberg.

That was 1997. The CNN Financial Network is long gone, but I’m still at Bloomberg, part-time, filing radio spots for Bloomberg stations in New York, Boston, San Francisco, and Washington, its broadcast services in Europe and Asia, and for syndication nationwide.

Our best friends in Washington include journalists we had worked with overseas, and others with analogous experience. When we travel, one of the boons of working for a world-wide news organization is that we can meet with well-informed colleagues in local bureaus. When the OPC publishes its next member directory, and the all-clear sounds for foreign travel, you can expect to hear from us.

If expatriates we meet working abroad hint that they might be ready to return to the States, our response tends to be: “Are you sure?”