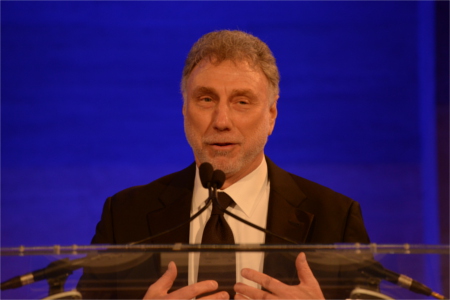

The following is a transcript of keynote remarks from Martin Baron, executive editor of The Washington Post, who addressed attendees at the OPC’s Annual Awards Dinner on April 18.

Thank you for inviting me to speak. Deepest congratulations to all the winners tonight – and to all the superb recipients of citations.

And, also, thank you for the day-to-day foreign reporting that consistently delivers on our most important mission: informing the public.

I want to make a point about the work we honor tonight. While this is journalism we admire, even more important it is work we need.

Americans need to know about the wider world they live in. Because of you, they can know, and they do.

In so many instances, you accomplish more than that. Often, you tell the citizens of other nations what their own press is forbidden to publish or broadcast.

Because their governments will impose harsh penalties . . . leveling crippling fines . . . denying access to the airwaves . . . barring purchases of paper needed to print . . . instigating politically engineered lawsuits. Or they will go further, jailing journalists . . . or having them killed.

Often paramilitaries act on the government’s behalf. Or crime syndicates, without a moment’s hesitation, will murder journalists and their families.

Government surveillance, in many countries, is a constant threat. Digital technologies, once seen as a liberating influence, are now transformed into weapons that silence and control.

For decades, the United States, through its government, proudly spoke up against repression like this – advocating for free expression, including a free press, in parts of the world that needed – and hoped — to hear our voice the most.

It did so, first, by showing respect for a constitutionally guaranteed free press in this country — even when it was angry over what was written or broadcast.

And it did so by embracing free speech and a free press worldwide, giving encouragement to citizens elsewhere who saw our First Amendment — and America’s democratic norms — as a model . . . as a cause for hope . . . as reassurance that their aspirations would be heard. That they would be supported by the most powerful nation on earth. Supported by its people. And supported by our president.

There was nobility in that global role for the United States. It meant we stood for something greater than our ourselves, a purpose that transcended our immediate self-interest. Free expression was a sacred principle, and it was often said then that American principles came first.

We understood what James Madison meant when he called free expression “the only effectual guardian of every other right.” We took to heart his argument for “freely examining public characters and measures” and “free communication among the people.”

Today, journalists and advocates of free expression around the world need us to live up to those foundational values. In too many places, they have little to hold on to. If our government proudly exports language that vilifies an independent press, we endanger them – and break faith with what we as a nation have long stood for. If we import that language from authoritarian regimes, we threaten what has kept us free.

The noble thing today would be to — once again –give the world’s independent press and its brave proponents of free expression this country’s historic gift: unwavering, unambiguous, forceful, principled support.

Tonight, here, we celebrate work that attests to the essential, invaluable contributions of a free and responsible press.

Because the world becomes an especially dangerous place when facts go missing, ignored, twisted or trampled on. Public conversation is poisoned. Policy-making rests on falsehoods.

We’ve seen the alternatives to objective facts, independently verified. We’ve seen them over the course of history, and we see them in the present day. They are unacceptable: Government propaganda rules, crackpot conspiracy theories proliferate, lies are spread to achieve ideological goals . . . pursue personal vendettas . . . accentuate tensions.

It is because of courageous journalists who can freely, honestly and forthrightly report what they learn . . .

. . . that crimes committed against the Rohingya in Myanmar have now been documented.

. . . that we could feel the struggle of migrants to get to this country’s border as well as the strains and separations that followed.

. . . that we became witness to a humanitarian disaster unfolding in Venezuela.

. . . that we could see the human toll of years of war in Syria and Yemen.

. . . that we could face up to the civilian deaths in Iraq.

. . . that we could see with our own eyes the rampant brutality of the drug war in the Philippines.

. . . that we know what life has become for young women who survived captivity under Boko Haram.

We learned all this because of superior journalism that was recognized with OPC awards this year and last. Because of intensely difficult, risky work that was needed to gather facts – news that was only too real.

Because journalists were doing their jobs in the two years when a president was casually, cynically – hundreds of times – going on about supposed “fake news.”

This is a poignant season for me to be giving these remarks, to reflect on intrepid foreign correspondents and the enduring value of their work.

A few weeks from now — May 9, specifically — will mark the 16th anniversary of the death of Elizabeth Neuffer, who was my vivacious, adventurous, generous and brave colleague at The Boston Globe. She was an experienced foreign correspondent, a mentor to others – whether they joined her in the cafeteria or in the field of war.

One of the most sorrowful things in my career was to inform the staff at the Globe that she was no longer with us. She was 46. She left behind her brother and her longtime companion, Peter Canellos, then the Globe’s Washington bureau chief, now with Politico.

Elizabeth died covering the war in Iraq. Her driver was traveling at a high speed because of the risk of abductions. He lost control. Along with Elizabeth, we lost her translator — Waleed Khalifa Hassan Al Dulaimi. He was 31.

Elizabeth had been fearless in investigating war crimes and human rights abuses overseas, publishing a much-honored book about Bosnia and Rwanda.

One human rights activist said at the time: “She had literally knocked on the doors of a couple of indicted war criminals that people had said couldn’t be found. They were there. Elizabeth found them.”

She also covered the first Gulf War, the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the war on terrorism in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and elsewhere.

Months after her death – the following October — I, along with other journalists and some officials of the George W. Bush administration, gathered at Gathland State Park in Maryland. There, four journalists became the first to be honored at a national monument since it was dedicated in 1896 to the writers and artists who covered the Civil War. Civil War battlefields are nearby.

Four reporters were recognized: Daniel Pearl, Michael Kelly, David Bloom, and Elizabeth.

Daniel Pearl, South Asia correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, was kidnapped and murdered in Pakistan, his throat cut by a senior al-Qaeda operative, his body dismembered.

Michael Kelly, then a Washington Post columnist and the Atlantic’s editor-at-large, became the first journalist to die in the Iraq war, killed in a Humvee accident with the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division.

David Bloom, with NBC’s “Today Show,” was the sixth journalist to die in Iraq, the second American. Most likely as a result of long periods spent in armored vehicles over weeks on assignment in Iraq, he developed a blod clot in his leg. It traveled to an artery in his lungs, killing him.

To repeat what I said then on behalf of those journalists:

“American democracy is nothing without them. For all the burdens they bear, the risks they take, and for all the difficulties they face overseas, they give us in return the ingredients that sustain a free society.

“Their coffins may not be draped in the American flag, but they are draped in America’s highest ideals.”

That October, 2003, ceremony in honor of journalists killed covering war was supposed to revive use of the National War Correspondents Memorial. The monument was built by George Alfred Townsend, the youngest correspondent to cover the Civil War, the first conflict to be covered extensively by independent reporters.

Finally, journalists were to be honored there once again.

Two years ago, I checked with Maryland state officials to see if anyone followed through on that idea. The answer was no. Those four war correspondents were the last to be honored. No names have been added to the monument since 2003.

Two conclusions from that: First, the contributions of brave journalists — losing their lives or their health or their freedom to inform the public — routinely go unrecognized or underappreciated. Second, we must not let that continue.

All of you have worried, as have I, about the safety of colleagues on dangerous assignments. They put themselves at risk not to make an ideological point but only with the simplest goal: to gather facts first-hand.

I recall visiting Anthony Shadid in 2002, then at the Boston Globe, after he was shot and wounded in Ramallah. Lying in a Hadassah hospital in Jerusalem, it was clear from the entry point of the bullet that he had narrowly escaped being paralyzed. And there were questions on that day as to whether he’d lose most of the mobility in one arm.

Of course, as we know, Anthony continued to report and to inform — because that is what he lived (and loved) to do, a mission as pure and public-spirited as can be.

He went on to report from Iraq, where he won two Pulitzers for The Washington Post. From Egypt, where he was harassed by police. From Libya, where he and three New York Times colleagues were arrested by pro-government militias, detained and physically abused. He died in 2012 while on assignment in Syria for The Times, apparently of an asthma attack. Our entire profession grieved.

When the president calls the press “enemies of the people,” I can think only of people who lived in service of the public’s right and need to know. I think of Anthony Shadid. Of Elizabeth Neuffer. Of the many goodhearted, dedicated people we all have worked with. I think of the sacrifices they made.

There is a reason we come to events like tonight’s that goes beyond collecting prizes, as outstanding as the work truly is. It’s not just that we come together. It’s that we stand together, in a spirit of shared purpose.

Competition is what gets us here. Common cause is what gives this event its true meaning.

If the last several years have left our profession feeling more vilified and more pressured, they have also, in my view, left us more committed and more united. With our colleagues in this country, with our fellow journalists around the world.

You could feel it in the collective fury over the savage murder in a Saudi consulate of Washington Post opinion writer Jamal Khashoggi. You could feel it years earlier at the expressions of relief when The Post’s Jason Rezaian was released on January 16, 2016, after 544 days in Iran’s notorious Evin prison, 49 nights in solitary.

You can feel it in the support for the indomitable Maria Ressa, now maliciously persecuted for practicing independent journalism in the Philippines.

You can feel it in the resolute support for Reuters journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, imprisoned in Myanmar for investigating the killing of 10 Rohingya Muslim men and boys.

You can feel it in the continuing call for justice in the murder of Malta’s Daphne Caruana Galizia, assassinated in a 2017 car bombing as she continued her tenacious investigations into official corruption.

You can feel it in how the memory of Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times is sustained years after her 2012 killing in Syria.

And you can feel it in the call for Syria to account for the abduction almost seven years ago of freelancer Austin Tice and to bring about his release at long last.

To be here tonight – to recite those names, to ask that we remember the many others like them, to honor your work, to recognize the inspirational daily courage of journalists, to be with you in this vital profession, to see us standing together – well, it is the greatest privilege.

Thank you for the opportunity.