At the end of two days judging, French veteran war photographer Patrick Chauvel surprised this year’s jury president Christiane Amanpour with a photo from his archives of her during the Bosnian War with a broken-down vehicle in the snow. Photo courtesy of Vivienne Walt.

by Vivienne Walt

For all the talk out of Washington about fake news and the press being the enemy of the people, there is always one small corner where foreign correspondents are revered every October: France’s medieval jewel of Bayeux. This year, the Prix Bayeux-Calvados, the weeklong festival for war correspondents, felt more urgent than ever in its 25th edition, a haven of people discussing the best frontline reporting of the past year, and showering praise on journalists working in the world’s toughest hotspots.

The jury of 47 journalists included OPC members Mort Rosenblum and myself, as well as 2013 John Faber Award winner Jerome Delay, who all spent three days in the northwest corner of Normandy viewing a stunning selection of photographs, and magazine and TV pieces. Iraq and Syria dominated the coverage, as they have for the past few years, but there was also in-depth reporting on Mexico’s cartels, the devastating war in Yemen, the Rohingya crisis, and conflicts in Ukraine and Sudan.

This year’s jury president was OPC member Christiane Amanpour, who kicked off our work with a moment’s silence for Jamal Khashoggi. Sadly, Khashoggi’s name will be added to next year’s plaque in Bayeux’s Garden of Remembrance, which bears the names of fallen journalists dating to the 1940s, and which is unveiled every year during the Prix Bayeux week. That’s just another feature that astonishes journalists arriving for the first time. “These are the only people in the world I know who care about war correspondents,” says Jonathan Randal, now 85, who began his career covering the Algerian War in the 1950s, and has served on the Prix Bayeux jury for 10 years. “I still cannot get over it.”

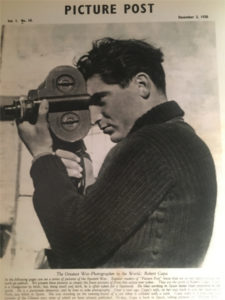

In the history of war exhibition in Bayeux, Normandy, a photo of Robert Capa, who is honored in the town with a memorial plaque.

A first-timer to Prix Bayeux, Amanpour told a packed auditorium of local residents, who had lined up early to get a seat at the Saturday night awards ceremony on October 13, that the event had amazed her. “Where else in the world would 1,200 people come listen to a discussion about Yemen?” she told a packed auditorium of locals, who lined up early on a Saturday night to get a seat at the awards ceremony on Oct. 13. “New York? No. London? I doubt it.”

There’s a good reason for Bayeux’s passion. It was the first town liberated from the Nazis in 1944, after Allied Forces landed on D-Day on the beaches a short drive away. Nearly 75 years on, the brutal battle that followed still defines this corner of France. “We felt we had a particular place in history,” Bayeux Mayor Patrick Gomont said in explaining why the awards are so important to the town. Because of that, Gomont sees one of the main functions of Prix Bayeux as exposing teenagers to the horrors of war – especially since locals who witnessed the D-Day battle in 1944 are fast dying out. So one category is chosen not by professional journalists, but by middle-school children, who review the work and vote. This year, the schools chose a 15-year-old student who herself who had fled Boko Haram in Nigerian, to present the prize; it went to France 2 Television for its report on child ISIS recruits. And a separate prize is chosen by Bayeux’s adult residents, who voted this year for Paula Bronstein’s work on the Rohingya crisis.

For the Mayor, involving the public – and especially the children – is crucial to making the Prix Bayeux an event that goes far beyond journalism. “What is important is to create citizens that are actors of tomorrow, with a global consciousness,” he said. For that reason, too, he is considering making permanent an extraordinary exhibition on the history of war reporting, which launched during this year’s Prix Bayeux and was curated by French journalist Adrien Jaulmes.

There were a few well-known names among the winners. CNN’s Nima Elbagir won the TV news award for her story on migrant slave auctions in Libya. But since entries remain anonymous until after the judging, there were some intensely heart-warming surprises, too. The prize for the young photographer of the year (those under 28) turned out to be 22-year-old Bangladeshi freelancer Mushfiqul Alam, whose wrenching black-and-white images of the Rohingya crisis brought a stunned silence inside the jury room.