The following is another installment in a series of reviews by William J. Holstein of a collection of books that were donated anonymously to the OPC in April.

The following is another installment in a series of reviews by William J. Holstein of a collection of books that were donated anonymously to the OPC in April.

by William J. Holstein

- Out of This World: Across the Himalayas to Forbidden Tibet, by Lowell Thomas Jr. Greystone Press, 1950.

- Seven Years in Tibet, by Heinrich Harrer, E.P. Dutton, 1954.

- The Silent War in Tibet: The Unknown Story of the Most Remote and Romantic Nation in its Struggle Against the Modern Might of China. by Lowell Thomas, Jr. Doubleday & Company, 1959.

These three books, which have recently come into the OPC’s possession, demonstrate just how long the Chinese Communist Party has been trying to eliminate the culture, language and religion of Tibet.

Chronologically, the first of these authors to enter Tibet was Heinrich Harrer an Austrian mountaineer and a member of Germany’s Nazi Party. As he and a team prepared to climb a mountain in Kashmir, World War II broke out and the British, then in control of India, captured him. He ended up in a British internment camp in India for five years before escaping and ending up penniless and in rags in Tibet in 1944. Even though they barred most foreigners, the Tibetans received him and a fellow prisoner warmly.

Harrer paints a fascinating portrait of daily life and festivals in Lhasa, which was surprisingly cosmopolitan with Nepalese, Gurkas, Ladhakis, Bhutanese, Mongolians and other tribes and nationalities represented. The Chinese did not exercise any control. Tibet was feudalistic but free, as it had been since the collapse of the Ching dynasty in 1912.

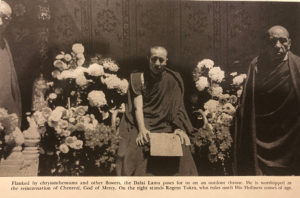

Toward the end of his seven years in Tibet, Harrer started tutoring the Dalai Lama. Then only 14, the Dalai Lama was worshipped as a god-king but did not exercise political control. A regent would do that until he became of age.

In 1949, the Chinese Communists under Mao Tse-tung won the long civil war against the Nationalists. The Communists argued that Tibet was a Chinese province, which the Tibetans did not accept. Recognizing their isolation from the international community and wishing for American support, the Tibetans accepted a proposal by Lowell Thomas, a famous travel radio broadcaster for whom the OPC’s radio award is named, to come with his son to visit in August 1949.

The Thomases were in Tibet for a week and had an audience with the Dalai Lama. They had modern still cameras and moving picture cameras, which few in Tibet had ever seen. (They also met Harrer.) After a perilous trek back out of Tibet, during which Lowell Thomas was thrown from his horse and his leg broken in eight places, they undertook a world-wide publicity campaign in favor of Tibetan independence. Harrer writes that the Thomases were the last foreigners to visit Tibet before the Red Army marched in in October 1950 against Tibetan troops armed with completely obsolete weapons. Resistance was impossible. The Chinese called it a “liberation” from the “imperialists.”

The Dalai Lama decided to try to continue to rule in the midst of a Chinese military occupation, but Harrer decided his time in Tibet was finished and left.

In The Silent War in Tibet, published in 1959, Thomas Jr. captures what happened in the following years. The Dalai Lama went to Beijing for a year to appease the Chinese, who were seeking to impose full cultural and political control over Tibet. In effect, they wanted to Sinicize the Tibetans, who were fiercely committed to their culture centered on Tibetan Buddhism. An armed revolt flared up and the Chinese retaliated. When it became clear that the Dalai Lama’s life was at risk, he fled to India in 1959. Thomas’s book captured many details of what happened from witnesses. He recognized the pattern of how the Chinese would seek to wipe out Tibetan culture by forcing some Tibetans to move to China and by sending millions of Chinese settlers into Tibet, outnumbering the Tibetan population.

Flash forward to today. Fragmentary reports suggest that the pressure on Tibetans to learn the Chinese language is intense. Tibetans have been forcibly moved out of their traditional homes into apartment buildings. Millions have been killed or have fled to other countries. The pattern now dominating the headlines about forced assimilation of the Uighurs in Xinjiang seems to have been perfected in Tibet. In my most recent contacts with the Tibetan diaspora, I have been asked: “You in the West care so much about endangered animal species in Africa. Why didn’t you care about us?”